I-81 Gives as Much as It Takes

This project was reported, written, produced and designed by Parker Butler, Isidro Camacho, Julia Gsell, Camille Hunt, Ellen Kanzinger, Leigh Lloveras, Mary Michael Teel and Abby Thornton.

By Camille Hunt and Isidro Camacho

It’s just past 9 in the morning. Butch Shields stands outside of Lee Hi Travel Plaza with a cigarette in one hand and a bottle of Mountain Dew in the other. This day, he will drive 15 hours. For now, he has stopped at Lee Hi for breakfast after dropping a load of plastic pipes in Buena Vista.

Off the beaten track and tucked away on Route 11 in the central part of western Virginia, Lee Hi Travel Plaza, is “almost like a secret truck stop,” as described by Corey Berkstresser, its general manager. Founded in 1958, Lee Hi predates the construction of I-81.

Lee Hi draws a specific crowd—local truckers who use it as a starting point for their day and seasoned truckers who know I-81 well enough to exit the highway for home-style food that tastes like their mothers cooked it.

Inside Lee Hi is Berky’s Restaurant, a greasy spoon open 24/7 that seems like it’s something out of a time warp. Jukebox hits from the 50s and 60s play over the speaker. Waitresses, who wear uniforms whose design hasn’t seemed to change in 30 years, offer customers coffee before they can make their way to a table.

Sitting in a booth with cracked vinyl seats, Shields hunches over a plate of steaming pork chops and scrambled eggs from the breakfast buffet. The clatter of knives and forks harmonizes with Frankie Valli’s falsetto as “Sherry” plays on the jukebox.

Shields loves to share stories about life on the road. He has just finished a blow-by-blow account of an argument between two truckers that played out over CB radio. It resulted in one bludgeoning the other with a hammer at an I-81 rest stop, he says. He calls them “CB Rambos” and erupts into wheezy laughter.

Times have changed for Shields and other long-distance truckers like him. These days, they are being replaced by “relay” drivers who transport shipments of goods part of the way before handing over the loads to another trucker who may or may not drive it all the way to the final destinations.

Shields is not a fan. He describes relay drivers as “9-to-5 truckers” whose inexperience poses safety hazards on the highway. “They drive a truck for six months, get scared and quit ‘cause they’re scared to be away from home from mama,” he said.

“Truck drivers don’t wear flip-flops or put the key up on the dashboard and play video games,” Shields said. “It’s a job. It’s not recreation.”

Everything about Shields is old school. His smile, framed by his graying horseshoe mustache, broadens when he’s asked about his career as a truck driver. He said he’s been on the road since 1981, driving an average of 825 miles a day for six months at a time. When he’s not on the road he enjoys fishing back home in Port St. Lucie, Fla.

As he talks and eats, other truck drivers head to Lee Hi’s buffet, most of them filling to-go boxes they take on the road. Shields’s cell phone erupts with the opening notes of “Sweet Home Alabama,” but he ignores the call to talk about his life’s work.

In his 36 years on the road, Shields said he has never gotten a ticket, or been in an accident.

Though he admits elements like ice can make driving tough, he still believes that “it’s not the weather. You just gotta adjust to the weather conditions.”

Nor is traffic the problem.

Ultimately, he said, it’s people who wreak havoc on the road, especially on a congested highway like I-81.

Thirteen miles northwest of Lee Hi is White’s Travel Center, another popular trucker destination.

Unlike Lee Hi, White’s is visible from the interstate, strategically located at the convergence of I-81 and I-64.

Berkstresser said the corridor between Lexington and Staunton is one of the busiest in Virginia. With just two lanes to drive on in either direction, trucks and cars compete for space.

The area’s high traffic is good for business; White’s serves about 5,000 customers per day and 600 trucks per night.

After expanding in 2014, White’s owners claimed that it became the largest on the east coast. It has what’s called “The Mall,” with a plethora of amenities that set it apart from other travel stops. Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen, Burger King, Iron Skillet and other restaurant chains satisfy hungry customers. A half-dozen shops sell everything from purses to pots to Petro oil.

White’s provides a home away from home for truckers. A barbershop and health clinic saves truckers from taking time off the road to make appointments. A motel offers truckers an alternative to living in their cabs. The truck stop also has a movie theater, arcade and green space adjacent to the building for entertainment and recreation.

And White’s was the site of the first travel center pharmacy in the nation.

Tim Wise, a 20-something trucker from western New York, is finishing up his lunch from the Iron Skillet.

Like Shields, Wise is a long-haul trucker. He said he drives 3,500 miles per week, 500 to 600 miles per day, and has never been in an accident. He hasn’t been home in two days, and his absences depend on where his shipments take him.

“Freight moves all over the country,” he said.

On this particular day, he’s hauling his trailer to Frederick, Md.

Wise’s travel rarely follows a set pattern. Sometimes he leaves on a Sunday night and comes back home on Wednesday. Other times his trips will only take two days, or he’ll be gone for 12-day stretches.

When he’s on the road, Wise sleeps in his truck. He takes a nine- or 10-hour break and starts driving again. “We keep the trucks moving,” he said.

He is paid a percentage of each mile he logs, which evens out to about 50 cents a mile. “If we’re not moving, no one’s making money,” Wise said.

The long-haul method of moving products is taxing on drivers and companies alike. Federal regulations restrict the number of consecutive hours a trucker can drive. If a trucker drives 70 hours within eight days, he has to take a 34-hour break before he can get back on the road. Truckers are required to keep logs of how many hours they spend on the road.

Robert “Bobby” Berkstresser, Corey Berkstresser’s father, said he’s seen an evolution in truckers during his 37 years in the travel center business.

Earlier in his career, he served mostly long-haul truckers. Today, most of his customers are relay truckers.

White’s location makes it ideal for the new breed of drivers.

A 12-million square foot Wal-Mart distribution center is located just 37 miles north on I-81. Several other major manufacturing plants are located within a 200-to-500-mile radius of White’s, Berkstresser said. That is a manageable distance for relay truckers to take on for a day’s drive.

“A relay driver has dinner at home,” Berkstresser said. “He has the opportunity to spend more time with his family. He has the lifestyle of someone who works in a factory, but he drives five-hundred miles a day.”

But he said the decline of long-haul drivers means more trucks on the road with more novices behind the wheel who pose safety hazards.

Shields agrees.

“It takes two to three years to learn how to master a truck,” he said. “It was a learning process; I made mistakes. I scared myself. I scared other people … I still learn sh**!”

By Julia Gsell and Leigh Lloveras

Rockbridge County Sheriff’s Deputy Chris Norris has been patrolling I-81 for over 20 years. “Deadly” is the word he uses to describe the highway.

The speed and volume of traffic on I-81 make it one of the most dangerous highways in America, he said.

I-81 is also popular among drug smugglers, particularly heroin traffickers, who use the highway for the same reason as everyone else—to get from north to south, and vice versa, as quickly and easily as possible.

The interstate is dangerous for everyone, but especially cops. Police cruisers pull out of hiding spots or shoulders of the road to pursue speeders. Cops risk getting hit by oncoming traffic when they step out of their cruisers and approach drivers.

“I used to flinch when the cars would come by and I’d get out to do a stop … I’ve even had to hug a car before,” Norris said.

When the sun starts to go down and evening traffic begins to build up, pulling people over isn’t always worth it, Norris said.

“Sometimes, we’re more of a hazard,” he said, “and we don’t want to create accidents.”

Routine traffic stops can quickly become dangerous, Norris said.

That’s why a large portion of police training prepares cops for these situations, in case they escalate, said Corinne Geller, a spokesperson for the Virginia State Police.

Norris said he has stopped many cars for speeding—and found drugs.

I-81 is so popular among smugglers that it’s known as the “Heroin Highway,” said Chris Billias, commonwealth's attorney for Rockbridge County and Lexington.

Dealers in Baltimore and other northeastern cities want to move heroin and other drugs “in the most efficient way possible to then distribute to smaller areas,” said Howard Hall, chief of the Roanoke County Police Department.

“You have to ask: ‘Why do we see truckers driving on that road?’ It’s the same reason (as with drugs),” Hall said. “Dealers are using it to get their product most effectively from point a to point b.”

Traditionally, Mexican black tar heroin has been distributed mainly in states west of the Mississippi, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s 2016 Heroin Report.

But in recent years, law enforcement authorities have seized more black tar heroin in the eastern part of the country.

I-81 has helped this expansion, authorities say.

As it heads west, Billias said, it has to get “from here to there somehow” and “we’re that pathway.”

Heroin, unlike marijuana, is hard to detect because most of it is transported in small doses, Hall said.

“You could put 1,000 doses of heroin in a shoebox. You don’t need even need a truck. It’s not going to be noticeable and it’s not going to smell,” he said.

Cops like Norris and Hall can only stop cars for violating a primary offense like speeding. If they can’t smell or see the drugs, they have no probable cause to search the car.

Undetected, drugs keep rolling down “the Heroin Highway.”

By Ellen Kanzinger and Mary Michael Teel

Rain pours on a two-mile stretch of road, but the sky is oddly clear.

With the press of a few buttons in a control room, researchers at the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute in Blacksburg can simulate just about any weather condition, including snow and fog.

They also use high-tech tools to pull off a variety of stunts that simulate driving experiences in the rain, sleet, snow and sunshine to gather information that could be used to improve car and highway safety.

VTTI’s Smart Road is reminiscent of the Test Track ride at Disney World. The institute’s researchers put drivers in real cars, unlike the virtual Chevy at the theme park, to study their reactions in life-and-death situations.

“I do feel that technology, in the broader sense, may help save us from ourselves.” Andy Alden, a senior research associate at VTTI

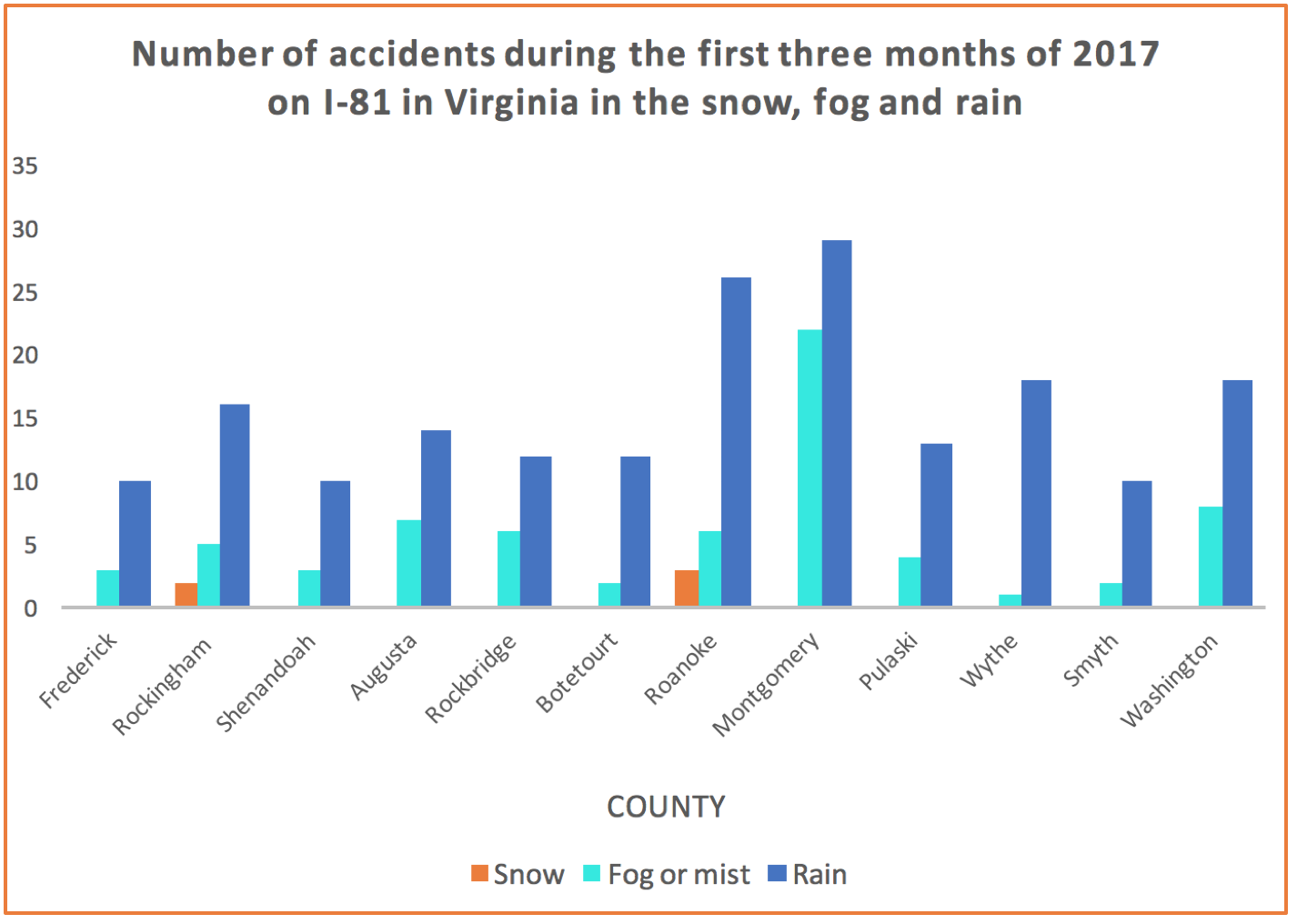

During the first three months of this year, the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles counted 1,931 accidents on I-81 in Virginia. VDOT also found that 35 percent of fatal accidents on I-81 involve a truck.

In essence, experiments conducted on the 2.25 miles of controlled access road provide hope for the highway and everyone who uses it.

That means that a large portion of the work continues to focus on the “human factor.”

Researchers test driver reactions to sudden obstacles in the road, which allows them to evaluate a vehicle’s tire and brake performance. Other scenarios include locking a car’s steering wheel to simulate mechanical failure.

In previous tests, researchers enlisted the help of a big stuffed animal, a St. Bernard on a remote-controlled skateboard that they steered into the path of drivers on the Smart Road.

The stuffed dog has had several names, including Roadkill and Hot Dog. The first nickname reflects the researchers’ dark humor. The second refers to heat packs researchers installed on the dog to track it on thermal cameras.

The experiment was eventually scrapped because it was too traumatic for drivers when they couldn't avoid hitting the “dog.”

“We do a lot of pretty creative things to set up circumstances to test how these systems work in the real world,” Alden said.

Other scenarios include throwing construction barrels and debris, such as mufflers, in front of cars to test the drivers' responses.

Alden said the institute is also testing drones to determine whether they can be used to monitor I-81, especially in surveying the scene of an accident.

Drones could be placed on posts along the highway and monitored by a traffic operations center. Alden said the information collected by drones could expedite police and EMT response to crashes and other emergencies.

By focusing on technological solutions to help make roads like I-81 safer, the researchers are working on alternatives to adding an expensive third lane to the highway.

Alden said I-81 is an ideal laboratory for testing technology of the future.

The significant increase in the number of vehicles on I-81 over the years is a major issue.

In 1975, the northbound portion of I-81, north of I-581 in the Roanoke area, had 21,250 vehicles on the road per day. In 2015, the same area saw 61,000 vehicles per day, according to VDOT.

A large part of that increase comes from the number of trucks on the road. Today, I-81 serves as one of the top eight trucking routes in the United States.

Jeff Lineberry, a VDOT director of transportation and land use, said trucks make up to 20 to 30 percent of traffic on some sections of I-81. Experts predict that traffic will continue to increase in the coming years.

The high ratio of trucks to cars on I-81 results in congestion and safety issues, Alden said. But it is not necessarily because truckers are bad drivers.

“Overall, we don’t see any evidence to say that the truck drivers are worse than the drivers of the cars, and a lot of times when we look at the video we see that some of the crashes that we think maybe were caused by the trucks, are actually the car behaving badly,” he said.

But it’s not really the car’s fault. It’s the driver’s.

Alden said there are five main reasons for car accidents. Most are related to distracted drivers who are:

The main issue with truck drivers is drowsiness or fatigue. Alden said when truck drivers talk on the phone, it’s often a good thing. It means they are awake and paying attention.

“While vehicles and roadway infrastructure have gotten safer in general, drivers have not. Driver distraction and impairment and other risky behaviors tends to negate the improvements made in the safety of vehicles and infrastructure,” he said.

Alden said removing human error would significantly help to improve safety on I-81. VTTI is working toward developing technology for Controlled and Automated Vehicles (CAVs).

It typically takes about 25 years for a fleet of cars to cycle into circulation across the country. Even if an automated car were to be introduced to the market today, it would still take another two and a half decades for the majority of the cars on the road to be completely automated.

Until then, cars and trucks must share the roads.

Because of the danger of mixed traffic sharing two lanes, some transportation experts and politicians have proposed adding a third lane to I-81. It would cost about $11 billion to add another lane to all 325 miles of I-81 in the commonwealth, according to VDOT.

I-81 also runs through a mountainous region, which makes it more difficult and expensive to build and operate the additional lane without blasting large sections of land.

For the time being, auxiliary lanes act as placeholders for third lanes in commonly congested portions of I-81, such as the areas around Roanoke and Harrisonburg. The lanes are short sections of widened road that are typically added at interchanges on highways.

I-81 needs more than technological advances. It also needs physical improvements.

Technology, Alden said, “will only take us so far. Given anticipated traffic growth rates, at some point we will need to build more roads.”

Highways are part of the fabric of American life. They also are vital to the economy. According to the American Trucking Association, trucks move $725 billion worth of products annually across America.

The U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics reported in 2015 that there were over 8.3 million trucks on the highways the year before. It said another 3.6 million trucks could be added to the roads by 2045, a 45 percent increase.

But the interstate system had an unexpected economic impact, especially in the smaller, more rural areas that were bypassed.

In a study done in 1996 on the effects of highway bypasses on rural communities, the National Cooperative Highway Research Program found that overall employment increased along the interstates.

But bypassing small towns hurt family-owned and operated businesses that relied on tourists getting on and off the highways. Travelers no longer needed—or wanted—to get off the road and explore.

Tom Camden, a native to the Lexington and Rockbridge County area, worked as a surveyor’s apprentice when the state first began construction on the interstate in the mid-1960s.

“Ultimately, I think it sort of was the death knell for small town America in terms of businesses and small family-owned operations,” he said.

By Abby Thornton

Spanning Virginia’s western border, I-81 can turn an otherwise pleasant Sunday drive into a road trip to hell. On this road, Mother Nature asserts herself with snow, rain, ice and ferocious wind.

Framed by the Chesapeake Bay to its right and the Blue Ridge Mountains to its left, Virginia’s location at the foot of the Mid-Atlantic region makes it a popular passage for travelers driving up and down the Atlantic Coast.

But the state’s natural features, while beautiful, contribute to a distinctive climate and terrain that can test even the best driver’s abilities.

In Virginia, I-81 crosses five drainage basins, or areas where precipitation falls and runs off into streams. Particularly at night, these streams work together with the mountainous terrain to create fog, which can make it difficult for drivers to see what’s in the next lane, let alone a sharp turn 300 feet down the road.

The frequent changes in elevation create a host of variable weather conditions—such as rain, sleet and snow—that can change from one side of a mountain to the next, said Sergeant Rick Garletts of the Virginia State Police.

“Any time you get around a mountain there’s an increased chance of weather,” he said. “When the weather comes in from the west and travels up those steep slopes, it causes the precipitation to change, and the mountain itself—its height—causes rain or snow. It can be sunny where you’re at and then a mile down the road it could be snowing or raining.”

Ron Gibbons, director of the Center for Infrastructure-Based Safety Systems at the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, said snow is a significant issue because many travelers are not used to driving in it.

“The weather changes significantly from the bottom end to the top end of the interstate, and the climate changes,” Gibbons said. “We have snow plows and all those things, but we don’t get enough snow that people are used to driving in it all the time. We sort of have this mix in population on I-81, so snow is generally something that we always have to be careful about.”

With higher elevations come colder temperatures, which can turn snow and water into ice, or worse, its devious cousin—black ice.

Butch Shields, 55, a trucker who grew up in Lynchburg but lives in Port St. Lucie, Fla., said snow is not an issue for him because he has driven in it for years. He said ice is his main concern when it comes to inclement weather. “It’s the most dangerous,” he said. “You can go, but you can’t stop.”

Gibbons and his crew have advanced machinery at the transportation institute that allows them to simulate the effects of different weather conditions—like snow and ice—on the roadway and analyze their effect on wheel spin and tire traction.

“In the visibility world, the inability to see through fog, rain and snow is critical,” he said. “If you’ve got a pedestrian on the side of the road, there’s a shorter detection distance for the driver.”

Poor visibility can quickly turn dangerous with the added threat of dangerous road conditions, said Gibbons.

“You’ve got a slippery road, you can’t see as far ahead because of the light scatter—particularly in the dark—and then you’ve got the pavement markings that disappear. People have a tendency not to slow down and just keep on going,” he said.

The specialists at the transportation institute spend much of their time searching for solutions to these issues by testing lighting features to see how they perform under weather conditions like snow and fog.

They run these tests at the Smart Road, a 2.2-mile-long test road on VTTI’s campus.

Owned by the Virginia Department of Transportation, the road was completed in 2001 and serves as a test lab for specialists at VTTI. Much of the technology VDOT implements is first tested on the road.

In recent years, VDOT has made a few changes to I-81 in an effort to alleviate some of the visibility issues caused by weather. The department has added flashing signals on some of the interstate’s sharper curves, and lowered the speed limit in other areas based on road and visibility conditions.

“The goal there is really to try and have people drive through the road at a safe speed and control those kind of issues,” Gibbons said.

He said his crew is also experimenting with active pavement markings—lines on the road that light up and shine in poor conditions.

Gibbons said VDOT is considering whether to install electronic message boards on other portions of I-81 that will warn drivers of hazardous conditions. But poor visibility and road conditions are just some of Mother Nature’s menaces.

Wind is another.

Every day, billions of dollars in goods and other products travel up and down I-81 in the backs of semi-trailer trucks. If they’re carrying light loads, their high profiles make it easy for the wind to catch them.

Inigo DeAristegui, who has driven trucks all around the country, said he’s seen plenty of big rigs tipped over on blustery days.

“If you’re lightly loaded, you can tip over. They tell us if you’re going 45 mph and you have a light load, it’s better to stop.”

DeAristegui said many of the accidents involving semi-trailers like his occur because people don’t know how to drive around trucks.

Trooper Garletts agrees that human recklessness is almost always a factor when accidents occur, weather-related issues aside.

“Human error is always going to be there,” Garletts said. “If you take a 16-year-old and put him on an interstate covered in an inch of snow, stats will show you that he’s going to have an issue. Smart decision-making is what we advocate. If you don’t need to go because of adverse weather, you probably need to stay at home.”

Modern technology has made it worse, he said.

“We’re in a smart age. Everybody has a phone now, radios, DVD players in the car that distract them from driving. Driver distraction is probably the biggest cause we have of crashes, even weather-related crashes.”

Garletts recalled an accident that occurred a little over a decade ago near Buchanan. A woman’s vehicle spun out into oncoming traffic and was T-boned by a semi-trailer. The woman was on her cell phone at the time of the accident.

Technology isn’t always the bad guy. With the help of cutting-edge technology, cars may soon be able to tell drivers when they’re approaching a slick spot on the road.

Back at the Smart Road, Gibbons and his crew stay busy testing new in-vehicle technology that will allow cars to detect foreign substances on the roadway—like black ice—and warn the driver.

VDOT has already begun the process of installing fiber optics on I-81 that will allow the infrastructure to communicate with vehicles.

But this technology is still years away from being implemented, Gibbons said.

Until then, Shields, the trucker, has a message for drivers: slow down.

“Accidents aren’t caused by the weather—they’re caused by the people,” he said. “They don’t slow down for the rain. They don’t slow down for the snow. It’s not the weather. You have to adjust to the road conditions.”

By Parker Butler

“Roland Brown is my name, and road kill’s my game.”

Road kill is one of the last things any driver wants to encounter on the highway. But it’s the norm in Virginia. Each year, the state ranks near the top in the number of deer-vehicle collisions.

As an assistant project manager for DBi Services, Brown has seen his share of road kill. DBi has a contract with the state to remove debris and animal carcasses from I-81.

Most deer-car collisions aren’t reported unless the driver has insurance that covers the damage, said David Kocka, a biologist at the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries.

“If you’re driving an old clunker, you won’t have that kind of insurance because it costs too much,” he said.

By law, Kocka said you don’t have to report hitting a deer unless the cost to repair the car exceeds $1,200.

Hitting a deer is also terrifying, as Mackey Dubay, 20, of Hartford, Conn., and her family found out when they were traveling on southbound I-81 last year and a white-tailed deer crossed their path.

“My mom was driving and I was in the passenger seat looking down at my phone,” she said. “The next thing I know she’s yelling and slamming on the brakes. I look up to see this massive animal bounce off the hood of our car and roll off the windshield.”

"Plain and simple: Just hit the deer." David Kocka, a state biologist

Between 2011 and 2016, only 625 deer-vehicle collisions were reported in Virginia, according to the State Farm Insurance Co.

But officials at the Virginia Department of Transportation suspect the number is higher. That’s because more than 60,000 deer carcasses are removed from the interstates in Virginia each year.

Bridget Donaldson, a senior VDOT research scientist, said it’s difficult to predict how a wild animal will behave, or where it will go. But she’s trying.

“No one really knows why deer jump out in front of cars. I think deer just haven’t evolved to understand that kind of speed. … They can see and hear cars, but they probably don’t understand the concept of a 70 miles-per-hour speed,” she said.

For the past two years, Donaldson and her team have been studying deer migration on I-64, which runs east-west through Virginia. They’ve placed cameras along the interstate in hopes of pinpointing the location and timing of animal movements.

She wants to place cameras along I-81 and to develop a system to warn drivers where the animals are and at what times of the day.

During deer mating season in late fall to early winter, DBi crews pick up 10 to 15 deer every day, Brown said. Most of the carcasses are taken to landfills in Augusta, Rockbridge and Alleghany counties.

"Deer hormones are racing so they’re thinking about other things, and not about the traffic," Kocka said.

Donaldson said deer seem to like areas along highways. There are often low tree branches and brush that deer feed on. But Brown said he thinks the deer gravitate to the highways because of the salt used to treat roads in the winter. The grass may taste better to deer, he said.

“If that body’s still warm by the time I get to it and it ain’t got too torn up, I’ll get whatever meat I can from the deer,”Joe Sellick, a DBi technician

DBi’s crews use an abandoned rest stop to hang the carcasses between two trees. There, they skin and clean them.

Road kill cleanup is messy and dangerous, as crews work on the shoulders of the highway with tractor-trailers, cars and SUVs flying by.

The job also has its bizarre moments, like the time an injured deer caused a commotion on I-81, Brown said. The deer’s back was broken, but the animal kept crawling in the median. A sheriff’s deputy showed up, pulled out his gun and started firing—while traffic whizzed by.

For Brown, the days can be tough, and the nights can be long, as he and his crews rush to remove dead animals and other debris to keep I-81 clear.